Understanding Cat Coronavirus Vaccine: Best 7 Expert Tips!

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is a common viral infection in cats, often harmless—but in rare cases, it can mutate into a deadly disease called feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). While a vaccine exists, its use remains controversial among veterinarians due to limited effectiveness and specific application guidelines. As a cat owner, understanding what the vaccine can and cannot do is essential for making informed health decisions. This guide offers clear, expert-backed insights to help you navigate the complexities of the cat coronavirus vaccine with confidence and care.

What Is Feline Coronavirus and How Does It Spread?

Feline coronavirus is a highly contagious virus that primarily affects the intestinal tract and spreads easily among cats, especially in multi-cat households or shelters. Most infected cats show no symptoms or only mild, temporary diarrhea—but the real concern lies in the virus’s potential to mutate.

- Common in Multi-Cat Environments:

The virus spreads through feces, shared litter boxes, food bowls, or grooming, making it widespread in catteries and shelters. - Usually Mild or Asymptomatic:

Up to 90% of infected cats experience no illness or only brief digestive upset before clearing the virus naturally. - Risk of Mutation to FIP:

In about 5–10% of cases, the virus mutates inside the cat’s body into FIP—a progressive, almost always fatal disease with no reliable cure. - Stress as a Trigger:

Immune suppression from stress, illness, or young age increases the chance of FIP development after FCoV exposure. - No Transmission to Humans or Dogs:

Feline coronavirus is species-specific and poses no risk to people, dogs, or other non-feline pets.

While exposure is common, actual FIP is rare—but devastating, which is why prevention strategies, including vaccination, are often discussed.

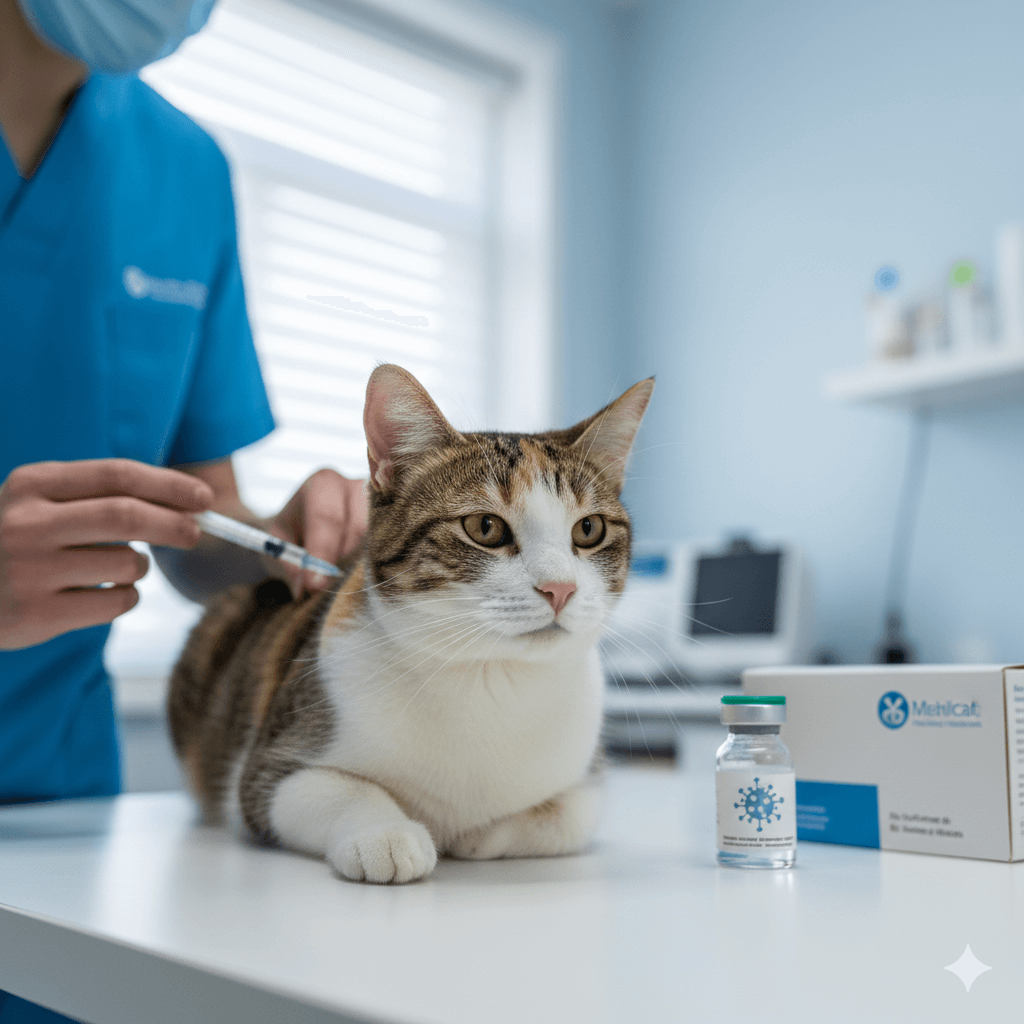

How the Cat Coronavirus Vaccine Works

The only commercially available feline coronavirus vaccine is a modified-live intranasal product designed to stimulate local immunity in the respiratory and upper digestive tracts. However, it must be administered before natural exposure to be potentially effective—a major limitation in real-world settings.

- Administered Intranasally:

The vaccine is given as nose drops, not an injection, to trigger mucosal immunity where the virus first enters. - Targets Only Certain Strains:

It’s formulated against one serotype of FCoV and may not protect against all circulating variants. - Requires Early Timing:

To be effective, it must be given before a cat is exposed—typically at 16 weeks or older, after maternal antibodies wane. - Not Effective in Already-Exposed Cats:

Since most cats encounter FCoV before 16 weeks, the vaccine often arrives too late to prevent infection. - Does Not Prevent FIP Directly:

The vaccine aims to reduce FCoV replication, but there’s no proven link to lower FIP rates in field studies.

Because of these constraints, many veterinary organizations do not routinely recommend the vaccine for all cats.

Check this guide 👉Cat Vaccine Side Effects: Best 7 Expert Tips!

Check this guide 👉Can I Give My Cat Vaccines Myself? Best 7 Expert Tips!

Check this guide 👉Understanding the FVRCP Cat Vaccine: Best 7 Health Tips!

Vaccine Considerations | Practical Realities |

|---|---|

Approved for use in cats 16+ weeks | Most cats are already exposed by 12 weeks |

Given as nasal drops | Requires handling cooperation; may cause sneezing |

Boostered annually | Limited evidence of long-term protection |

Marketed as FIP prevention | Does not reliably prevent FIP development |

Low risk of side effects | Generally safe but debated clinical value |

When Might the Vaccine Be Recommended?

While not part of standard core vaccines, there are specific scenarios where a veterinarian might suggest the feline coronavirus vaccine—usually in controlled, high-risk environments with careful planning.

- Catteries or Breeding Facilities:

In settings where new kittens are constantly born and FCoV is endemic, some breeders use the vaccine as part of a broader prevention strategy. - Shelter Intake Protocols (Rare):

A few shelters with known FCoV outbreaks may consider vaccination for incoming adolescents—if exposure history is unknown. - Cats Entering High-Risk Group Housing:

If an FCoV-negative adult cat must join a multi-cat household with known carriers, vaccination may be discussed cautiously. - Travel to High-Prevalence Regions:

In rare cases, international travel to areas with documented FIP clusters might prompt a risk-benefit discussion. - Owner Request After Full Counseling:

Some owners opt for the vaccine after thorough education about its limitations and realistic expectations.

Even in these cases, vaccination is always paired with superior hygiene, stress reduction, and FCoV testing—not used alone.

Limitations and Controversies Around the Vaccine

The feline coronavirus vaccine remains one of the most debated tools in feline medicine. Major veterinary bodies, including the American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP), classify it as “not generally recommended” due to inconsistent evidence of benefit.

- Lack of Strong Clinical Evidence:

Field studies have failed to show a significant reduction in FIP cases among vaccinated cats in real-world conditions. - Timing Challenges:

Since FCoV exposure often occurs before 12 weeks, the vaccine’s 16-week minimum age makes it ineffective for most kittens. - No Impact on FCoV Shedding:

Vaccinated cats can still become infected and spread the virus, offering no herd immunity benefit. - False Sense of Security:

Owners may mistakenly believe their cat is “protected from FIP,” leading to relaxed biosecurity in multi-cat homes. - Resource Allocation Concerns:

Veterinarians often prioritize proven interventions—like parasite control and core vaccines—over this low-yield option.

Until more effective FIP prevention tools emerge, management—not vaccination—is the cornerstone of control.

Effective Alternatives to Vaccination for FCoV/FIP Prevention

Because the vaccine has limited utility, most experts focus on practical, evidence-based strategies to reduce FCoV transmission and FIP risk—especially in multi-cat settings.

- Limit Group Size:

Keep cat groups small (ideally under 5) to minimize viral circulation and stress-related immune suppression. - Frequent Litter Box Cleaning:

Scoop boxes at least twice daily and disinfect weekly—FCoV survives in feces for up to 7 weeks in dry environments. - Separate Litter and Feeding Areas:

Use separate boxes and bowls for each cat to reduce fecal-oral transmission. - Test and Isolate New Arrivals:

Use PCR fecal testing to identify FCoV shedders before introducing new cats to a household. - Minimize Stress:

Provide enrichment, hiding spots, and predictable routines—stress is a known trigger for FIP development.

These measures are far more impactful than vaccination in preventing both FCoV spread and FIP progression.

Special Considerations for Kittens and High-Risk Cats

Kittens between 3 and 16 months are at highest risk for FIP due to immature immune systems and frequent exposure in shelters or catteries. While the vaccine isn’t ideal for them, other protective steps are critical.

- Maternal Antibodies Offer Temporary Shield:

Kittens nursing from immune mothers get short-term protection—but become vulnerable after 5–7 weeks. - Avoid Early Weaning in Catteries:

Keeping kittens with mothers longer may delay exposure until their immune systems are stronger. - Monitor for Early FIP Signs:

Lethargy, fever unresponsive to antibiotics, weight loss, or fluid buildup warrant immediate vet evaluation. - New Antiviral Treatments Offer Hope:

Drugs like GS-441524 (where legally available) show remarkable success against FIP—but prevention remains preferable. - Do Not Vaccinate Exposed Kittens:

If a kitten already tests positive for FCoV, the vaccine provides no added benefit and is not recommended.

Proactive care—not vaccination—is the best defense during this vulnerable life stage.

Expert Insights: What Veterinarians Wish Owners Knew About Cat Coronavirus

While the topic of feline coronavirus and FIP can feel overwhelming, veterinarians emphasize a few key truths that can empower cat owners to make calm, informed choices. These professional insights cut through the noise and focus on what truly matters for long-term feline health.

- Vaccination Is Not a Magic Shield:

Most veterinary specialists agree that the current coronavirus vaccine should never replace strong biosecurity practices—it’s not a standalone solution. - FIP Diagnosis Has Improved Dramatically:

Thanks to advances like RT-PCR testing and the availability of antiviral treatments (where legal), FIP is no longer an automatic death sentence in many regions. - Asymptomatic Shedding Is Normal:

A cat testing positive for FCoV isn’t sick—it’s simply exposed. Lifelong shedding can occur without ever developing FIP, so avoid panic or unnecessary rehoming. - Multi-Cat Homes Can Be Safe with Smart Management:

You don’t need to keep only one cat. With proper litter hygiene, low stress, and small group sizes, many multi-cat households remain FIP-free for years. - Prevention Starts with the Litter Box:

Over 80% of FCoV transmission happens through fecal contact. Scooping twice daily and using dedicated litter boxes per cat are the most effective preventive steps you can take.

Understanding these realities helps shift the focus from fear to proactive, compassionate care—exactly what your cat deserves.

Frequently Asked Questions About Cat Coronavirus Vaccine

Does the feline coronavirus vaccine prevent FIP?

No—it aims to reduce FCoV infection but has not been proven to reliably prevent FIP in real-world settings.

Is the vaccine safe?

Yes, it’s generally safe with mild, short-term side effects like sneezing or nasal discharge after administration.

Should I vaccinate my indoor-only cat?

Almost never. Indoor solo cats have extremely low FCoV exposure risk, making vaccination unnecessary.

Can vaccinated cats still get FIP?

Yes. Many vaccinated cats have developed FIP, confirming the vaccine’s limited protective effect.

Are there better ways to prevent FIP?

Absolutely—focus on small group sizes, strict litter hygiene, stress reduction, and avoiding overcrowding.

Making Informed Choices for Your Cat’s Health

When it comes to the cat coronavirus vaccine, knowledge is your most powerful tool. While it exists as an option, its real-world impact is minimal compared to thoughtful husbandry and environmental management. By prioritizing cleanliness, minimizing stress, and understanding your cat’s individual risk, you create a safer, healthier life far beyond what any vaccine can offer. Always consult your veterinarian for personalized advice—but come prepared with questions and a clear understanding of what the vaccine can and cannot do. In the end, your love, attention, and proactive care remain the true foundation of your cat’s well-being.

Understanding Cryptosporidium in Cats: Best 7 Expert Tips! – Spot symptoms, treat safely, and stop parasite spread in your home.

Understanding Cryptosporidium in Dogs: Best 7 Expert Tips! – Learn symptoms, treatment & prevention for this stubborn gut parasite.

Understanding Syringomyelia in Cats: Best 7 Expert Tips! – Recognize signs, manage pain, and support your cat’s neurological health with vet-backed guidance.

Understanding Syringomyelia in Dogs: Best 7 Expert Tips! – Expert insights on symptoms, MRI diagnosis, pain management & quality of life.